Mast cells may explain chemical intolerance

Image by Kauczuk

A newly published paper, co-authored by IDSS Professor Nicholas Ashford, also a visiting scientist at the Harvard Chan School of Public Health, provides a long-sought link between environmental exposures and conditions like Gulf War syndrome, breast implant illness, chemical intolerance and possibly even long-haul COVID-19. This discovery represents a major step toward improved diagnosis, treatment and prevention.

The new study by researchers at The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, as well as the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the AIM Center for Personalized Medicine, supports mast cell activation syndrome and mediator release (MCAS) as an underlying mechanism for chemical intolerance. This new paper is a companion publication to the publication of a paper describing chemical intolerance (see below).

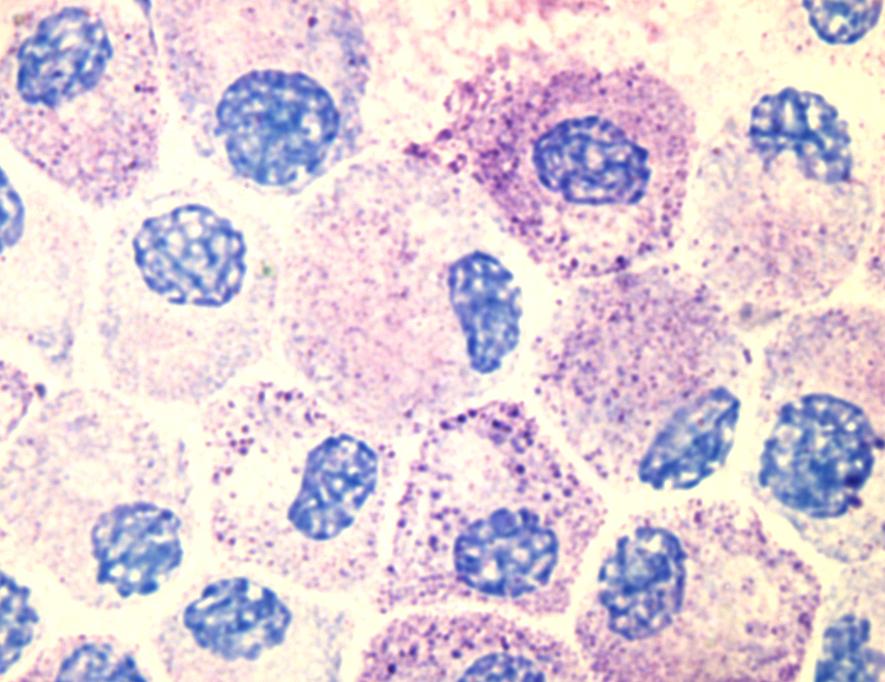

Mast cells are considered the immune system’s “first responders.” They originate in the bone marrow and migrate to the interface between tissues and the external environment where they then reside. When exposed to “xenobiotics,” foreign substances like chemicals and viruses, they can release thousands of inflammatory molecules called mediators. This response results in allergic-like reactions, some very severe.

These cells can be sensitized by a single acute exposure to xenobiotics such as pesticides or solvents, or by repeated lower-level exposures, such as breathing volatile organic compounds (VOCs) associated with remodeling or new construction. Thereafter, even low levels of those and other unrelated substances can cause the mast cells to release the mediators that can lead to inflammation and illness.

Although mast cells were identified more than a century ago, only in the past 10 years have researchers described Mast Cell Activation Syndrome (MCAS).

“Advancing our understanding of mast cells offers the potential to predict, prevent and treat many exposure-induced illnesses,” said Claudia S. Miller, MD, MS, professor emeritus in the department of family and community medicine at UT Health San Antonio, and lead author of the study. “This understanding opens a new window between medicine and environmental exposures.”

Environmental Sciences Europe, a journal reaching regulatory toxicologists worldwide, published the study Nov. 18 of this year and a prior companion paper in which Professor Ashford contributed to a study that demonstrates evidence of the mechanism for how and why people develop unexplained intolerances to chemicals, foods and drugs. Findings are published in May of this year online in the journal Environmental Sciences Europe.

Although intolerances to certain chemicals affect 15 to 30 percent of the U.S. population, the causes have not been well understood. However, more recently, researchers have described a two-step process of “toxicant-induced loss of tolerance” that links certain groups of chemicals to the onset of intolerance. The “initiation exposure event” involves either a single major exposure incident or repeated low-level encounters with chemicals such as pesticides and smoke, as well as chemicals found in newly renovated buildings and moldy environments. “Triggering” is the second stage, when individuals experience debilitating symptoms, including fatigue, headache, weakness and rash, when exposed not only to the chemicals that initiated their illness, but also to unrelated foods and drugs at levels that never bothered them before.