Economics for hard times

Peter Dizikes | MIT News Office

November 11, 2019

Economists, on the whole, favor open immigration and free trade policies, which they regard as catalysts for economic growth. But as polling shows, many people in the U.S. and Europe disagree. They are wary of losing jobs and earning power where there is immigration, and they believe free trade pushes industry abroad. So who’s right, the economists, or the people?

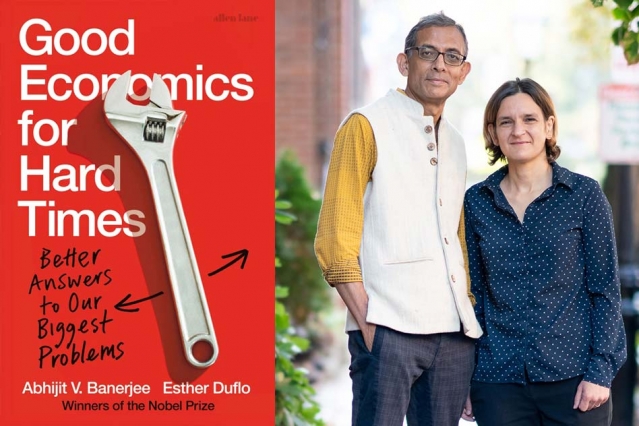

Well, according to MIT’s newest Nobel Prize laureates, economists Esther Duflo and Abhijit Banerjee, each side gets one count right and one wrong.

“If you look at the best evidence, it tells us that economists’ view of migration is more correct,” Duflo says. “It is not a big problem to let more migrants in.” Study after study shows that increased immigration does not affect wages, for instance. And the presence of migrants tends to let more women who are longtime residents enter the work force.

Okay, what about trade?

“On trade it is the opposite,” Duflo says. “The evidence shows that people’s instinctive view of trade, that it does hurt them, has a lot that is true about it, and economists’ instinctive view on trade, that it should be good for everyone, is not correct.”

Although free trade boosts overall growth, it also produces concentrated pockets of job losses. And while economic theory has long held that displaced workers will move to new job opportunities, this rarely happens. In countries that started trading with China during the last two decades, for example, the working-age population has not decreased in the areas most hard-hit by imports from China.

What the mistaken ideas about both immigration and trade ignore, Banerjee says, is the “stickiness” of real life. Most people do not want to uproot themselves.

“One thing that ties those two issues together is the idea of stickiness,” Banerjee says. “Ordinary people like to stay in place. [Economists] think trade should be fine because, yes, it could hurt some people, but people are going to move to other jobs in other places. But people are very reluctant to do that. They don’t want to go to a different sector and a different place and a different life.”

Until recently, these were not the kinds of issues Banerjee and Duflo often discussed. But now, in their second book, “Good Economics for Hard Times,” published today by Public Affairs Press, the MIT duo examines large-scale, politically fraught issues with economic implications, including immigration, trade, social identity, inequality, automation, and more.

In each case, the book examines what empirical research tell us about the world — as well as the limits of our knowledge. Only on that basis, Banerjee and Duflo suggest, can we think effectively about economic policy.

Or, as the authors write in the new book, “The world is a sufficiently complicated and uncertain place that the most valuable thing economists have to share is often not their conclusion, but the path they took to reach it — the facts they knew, the way they interpreted those facts, the deductive steps they took, the remaining sources of their uncertainty.”

Scaling up

The new work by Banerjee and Duflo follows “Poor Economics,” (PublicAffairs, 2011), their first book, which focused on helping the world’s 1 billion poorest people, who exist on the equivalent of $1 per day.

“Poor Economics” stemmed from research Banerjee and Duflo have created and facilitated as co-founders (with Sendhil Mullainathan) of MIT’s Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL), a leading antipoverty research network. These smaller-scale, empirical projects are what won Duflo and Banerjee the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences last month, which they shared with Michael Kremer of Harvard University.

By contrast, “Good Economics for Hard Times” examines issues of global scale, while maintaining the authors’ taste for empiricism. Trade is a hotly debated issue, but how much does it contribute to growth? As the authors note, it produces a notably modest benefit in the U.S., where it equals about 2.5 percent of GDP, no more than what a good year of growth is worth.

Similarly, while immigration stereotypes abound — think of the “Polish plumber” who supposedly takes away fix-it jobs from the British or French — people do not migrate as often as the popular perception suggests. About 3 percent of Greeks have left the country this decade, despite unemployment rates reaching as high as 27 percent and the presence of open borders in the European Union.

“The Polish plumber is an iconic figure in France but lives mostly in Poland,” Duflo says.

To be sure, large sections of “Good Economics for Hard Times” focus on other issues. In one chapter, Banerjee and Duflo contend that people’s sense of ethnic or partisan identity is more flexible than is often assumed. If so, that would be good news for some policy advocates. In many countries, ethnic or political divisions can create a barrier to public spending if people are unwilling to be taxed for the sake of other social groups. But Banerjee and Duflo suggest that a significant part of this is a public-perception problem.

“At the core of this is a lie,” Banerjee says. “And I think we have to start by saying that. It’s just not true that all federal and state spending goes to ‘other’ people. There’s a lot of polarization that was created by such lies, and while we won’t fix these prejudices in a day, I do think it’s worth pushing back.”

As Duflo points out, it is also tough to establish cause and effect when examining why some governments tax and spend more than others.

“It’s true the U.S. is a diverse society and Denmark is not diverse, and Denmark has much higher taxes than the U.S.,” she says. “But I’m not sure whether that comes from the fact that Denmark is [more socially homogenous] or from the fact that the government as an enterprise is [seen as] a more legitimate enterprise generally.”

“We have much more to learn”

While the intent of “Good Economics for Hard Times” may be to get people to think sharply about pressing problems, Banerjee and Duflo also discuss the kinds of policy interventions they think are promising. Some of these aid people in “transitions” during life, especially job loss. These transitions have significant social impact; research shows that people who lose jobs after age 50 have lower life expectancy than those who keep working. In a rapidly-changing economy, we need to worry about the many people who will have a hard time in the labor market.

“The idea that people are going to find the opportunity, left to themselves, is implausible,” Banerjee says. “”[Our] view is we need to act on this collectively: You aren’t a failure because you lost your job. This is a transition. It’s society’s problem rather than only yours.”

While there are a variety of policy measures to do this — such as improved Trade Adjustment Assistance for people displaced by trade-induced job losses — Banerjee and Duflo also favor what they call the “somewhat radical idea” of subsidizing entire firms and older workers affected by trade, keeping them in business and at work, respectively. A robust effort to do this, they write, would help “prevent communities from falling apart” when firms struggle.

And, as Duflo says, “People don’t want just money. They want dignity. Giving them that is not betraying some deep philosophical principle.”

For this reason, the authors are more skeptical of universal basic income proposals; as they note, U.S.-based surveys shows that about 80 percent of workers have a strong sense of satisfaction, usefulness, or personal accomplishment tied to their jobs and careers.

Perhaps more conventionally, Banerjee and Duflo also strongly favor greater support for “labor-intensive public services” such as public education and care for the elderly. Crucially, these kinds of jobs are unlikely to be either replaced by technology, or outsourced to another country, since they are firmly situated in particular places.

As “Good Economics for Hard Times” also points out, a wealth of research strongly suggests the high social value of, say, early childhood education; such investments would clearly pay for themselves, on a society-wide basis.

In all cases, Banerjee and Duflo write, “The goal of social policy, in these times of change and anxiety, is to help people absorb the shocks that affect them without allowing those shocks to affect their sense of themselves.” And, as they note, “we clearly don’t have all the solutions, and suspect that nobody else does either. We have much more to learn. But as long as we understand what the goal is, we can win.”